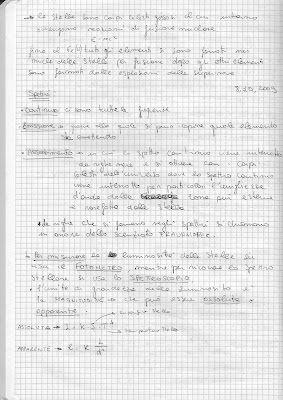

martedì 27 ottobre 2009

giovedì 22 ottobre 2009

Appunti inglese

Appunti Latino

mercoledì 21 ottobre 2009

giovedì 15 ottobre 2009

lunedì 5 ottobre 2009

Hans Holbein Gli Ambasciatori

MODULO 1

INTRODUZIONE AL TEMA DELLA VANITAS, ORIGINI E ANTECEDENTI.

"Un infinito vuoto, dice Qohèlet.

Un infinito niente.

Tutto è vuoto niente"

(Ecc., 1,2, trd.Ceronetti)

Nell'ambito della natura morta del 1600, il tema della transitorietà della vita terrena, legato al biblico ammonimento che incita al disprezzo delle cose terrene, trova compiuta espressione nel genere pittorico della cosiddetta "Vanitas".

In principio questo genere pittorico venne dunque inquadrato all'interno di un contesto religioso e la morte, presenza costante, era vista positivamente, come mezzo per ottenere la vita eterna e la vera felicità al termine di un'esistenza trascorsa tra le insidie del peccato.

Oggigiorno possiamo considerare

Probabilmente il collegamento fra arte e "memento mori" in questo genere pittorico è motivato dall'austero spirito della controriforma, dalle pestilenze che accompagnarono la guerra dei trent'anni, o ancora dall'insegnamento gesuitico e dalla meditazione sulla morte.

Il genere nasce nel severo ambiente olandese (calvinista) per poi diffondersi ai paesi (controriformati) Spagna, Italia, Francia.

Il panorama pittorico complessivo consente di individuare le specifiche caratteristiche nazionali con cui questo genere si è manifestato, adattandosi ai diversi contesti culturali e religiosi.

Si passa così dalle prime austere composizioni olandesi, permeate di rigore calvinista, alle più grandiose e decorative espressioni fiamminghe, vere mostre di vanità terrene, al complesso simbolismo delle vanità spagnole, accese di mistico fervore e di fin troppo macabro realismo.

QUALCHE NOTIZIA DI CARATTERE TERMINOLOGICO

"Vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas" (Ec., 1,2) recita l'Ecclesiaste affermando la vanità di tutte le cose terrene: potere, fama, ricchezze, la stessa sapienza, tutto è vanità, tutto è soffio di vento.

L'origine del termine "Vanitas" è da ricercare dunque nella locuzione latina contenuta nel testo biblico dell'Ecclesiaste. L'originario termine ebraico hèvel, tradotto con il vanitas latino, ha il significato più specifico di fumo, vapore, inconsistenza.

Secondo Ceronetti (1980) l'esatto termine latino corrispondente a hèvel non sarebbe vanitas ma lebes, cioè rovina, distruzione, fluire eterno delle cose.

Per quello che riguarda invece la dizione italiana"natura morta", essa deriverebbe da una cattiva interpretazione dell'espressione "nature inanimèe" usata da Diderot a proposito della pittura di Chardin ed ha, in origine, una valenza negativa e critica nei confronti di un tema periferico rispetto a quelli accreditati dalla tradizione accademica.

CLASSIFICAZIONE E INTERPRETAZIONE DEI PRINCIPALI SIMBOLI ALLEGORICI

L'allegoria, figura retorica della letteratura, viene impiegata in arte per esprimere un significato riposto, diverso da quello apparente, questo nel passato quanto nel presente. Fu largamente usata nel 600, sia per alludere a significati laici o profani, ma anche per suggerire riflessioni religiose. Non a caso uno dei temi più ricorrenti fu quello del santo o del filosofo che medita sulla morte .

Il repertorio fondamentale di immagini e simboli che costituisce l'efficace linguaggio della Vanitas è principalmente formato sulla autorevole base delle Sacre Scritture, si è poi arricchito attraverso altri testi illustrati, quali le Artes moriendi, in cui il severo richiamo ai valori eterni dell'esistenza trova un buon mezzo di espressione nel contrasto tra l'agire umano e la vanità del mondo, ma ha saputo cogliere dal quotidiano gli spunti più specifici e distintivi del suo linguaggio

Panofsky scrive " nessun periodo è stato tanto ossessionato dalla profondità e dalla vastità, dall'orrore e dalla sublimità del concetto di tempo quanto il barocco". Seguendo le sue indicazioni capiamo che la figura del tempo "distruttore" di ogni cosa terrena entra in relazione con l' iconografia della morte.

Nella Vanitas la presenza del teschio ha un ruolo importante, è simbolo della transitorietà della vita, ma l'incombenza della morte sulla vita si allaccia anche all'iconografia della clessidra e dell'orologio.

Lo studioso Veca ha classificato alcuni oggetti della composizione Vanitas come indicatori" rispetto ad altri, essi producono cioè un degrado rispetto agli oggetti "indici"(libri, candele, calici ecc..).

Gli oggetti "indicatori" sottolineano il corrompersi delle cose materiali grazie all'azione livellatrice del tempo.

Gli oggetti servono ad inviare "un messaggio" che spesso è evidenziato grazie alla presenza esplicita di un cartiglio sul quale sono presenti motti o citazioni ( vanitas vanitatum, homo bulla, mors omnia vincit, memento mori e così via..).

La composizione della Vanitas ruota quasi sempre intorno alla figura del teschio e la classificazione degli oggetti dei repertorio abituale si possono dividere secondo Bergstrom in tre gruppi:

| ESISTENZA | ALLUSIONE | SIMBOLI CHE |

| TERRENA. | U1-1 ALLA | OFFR0 1` UN |

| (scomposta in 3 | FUGACITA' | SPERANZA DI |

| sottogruppi) | DELLA VITA | SALVEZZA.RESURRE |

| | TERRENA. | ZIONE |

| I -VITA CONTEMPLATIVA. Libri, strumenti usati | Teschio, clessidra, orologio | conchiglie |

| nelle arti o simboli | (scorrere del | |

| della letteratura, della scienza, della musica. | tempo) | |

| 2-VITA PRATICA Borsette, gioielli, oggetti di valore, armature. Queste | Candele, lampade a olio (vita trasformata in | Spighe di grano |

| cose denotano: | fumo) | |

| ricchezza, gloria, potere. | Bolle di sapone | |

| | (inconsistenza) | |

| 3-VITA | Fiori (di solito | |

| VOLUTTUARIA | rose e | Alloro (fama oltre alla |

| Pipe, articoli da | anemoni) | morte) |

| fumatori, bicchieri di | Frutta | |

| vetro, strumenti | (in via di | Edera |

| musicali, carte da gioco. | disfacimento) | |

| Alludono ai piaceri della vita. | | |

| | | |

| | | |